Our topic of immigration effects on women will cover an extensive amount of women’s issues as they pertain to status including but not limited to: migrants, asylum seekers and refugees. Our rationale for this stems from the desire to learn more about the issues women face as a result of immigration and the power dynamics it entails such as sexual violence, trauma, labor, poverty, motherhood, and health. We believe that the testimonies of different women along various borders will help to solidify a common understanding of why and how women choose to migrate, and the prices to be paid for the prospects of a better life. We will see if there are aspects connected to gender on why some women choose to immigrate and obstacles that they face. We will investigate why these women, despite all the risks, choose to try to immigrate and how this is linked to their gender. The biases that come with being a female immigrant will be explored and the possible benefits and disadvantages that come with this. Our focus is Latin American women immigrants that crossed the U.S. Mexican border.

Immigrant Women’s Labor and Its Effects

Immigration in the United States has been a controversial topic for several years, especially concerning the influx of immigrants from Latin America. One of the multiple reasons that draws immigrants to the United States is the prospect of better employment. Men and women alike immigrate in search of improved job prospects, however these wishes are not always so easily fulfilled. Often, immigrants take on undervalued, low-skill jobs that affect their social life and citizenship status, disproportionately so for women. The gender bias and strict laws that exist within the immigration system disadvantages women as well as the dependents in their lives by forcing women to work low-wage jobs in poor conditions or not allow her to work at all.

In recent decades, the United States has undergone a dramatic transformation of its industrial and employment structure. Neoliberal emphasis on free trade, deregulation, and flexibility have contributed to rising inequality and a continual erosion of work conditions. Non-standard work arrangements, such as on-call work, temporary help agencies, subcontracting, and part-time employment have all grown at rapid rates, causing the serious detriment of wages and job quality. Women entering the labor force in developing nations may not find open positions because of these recent neoliberal policies increasingly adopted by many nations (Moghadam 57). Many Latin American immigrants find themselves in this position and look towards other nations with more job opportunities, such as the global North. Demand for cheap labor in the global North affects employment as well as residential outcomes for immigrant Latinas.

Part of what constitutes the need for cheap labor is the demand for female immigrant labor and the globalization that contributed to the increase of U.S. manufacturer’s employment in developing countries. Along with the explosive growth of service work and “care-labor” in child and health care, this has dramatically increased the demand for low-skill immigrant women’s labor. Immigrant women workers tend to work as maids and housekeepers, registered nurses, home health aides, cashiers, and janitors. They also comprise more than half of all workers in the agricultural sector, and almost forty percent of textile and garment production workers (AmericanImmigrationCouncil). These women perform essential, yet undervalued jobs that countless people depend on during their daily lives. However, because these jobs tend to be poorly paid, immigrant women continue to be disproportionately affected by this underappreciation of labor.

As the concentration of immigrants in the low-wage market grows, the working conditions of that sector will most likely not improve to a higher standard. It is expected that with increased access to education, work opportunities should improve for educated and experienced workers, allowing educated immigrant women to become preferred workers as compared to their non-educated and inexperienced counterparts. Statistics show more than one-third of immigrant women workers have a bachelor’s degree or more, less than one quarter have some college education short of a bachelor’s degree, and around forty percent have a high-school diploma, equivalent, or less (ImmigrationImpact). However, the unique characteristics of the low-wage labor market, particularly areas where immigrant women are concentrated, may constrain the role of human capital in shaping employment prospects. Immigrant women are highly segregated in a handful of occupations and industries that are characterized by low wages and subcontractors. However, these laborers are increasingly being replaced by machines and other technologies that allow companies to produce goods for fractions of the costs of what they are paying these already low-wage workers. For example, improvements in technology in the textile industry have replaced women’s manual labor. If manual laborers are to be rehired, typically men are the first to be recruited over women (Moghadam 58). Workers are being driven to look elsewhere for possible job prospects, bringing many to the global North, especially Latina immigrants to the United States. Therefore, declining business in the low-skilled labor markets of developing countries of the global South that typically produce quickly and cheaply made goods, have heightened the demand for immigrant labor in countries of the global North.

IMMIGRATION LAW AND ITS EFFECTS

Immigrants in the labor force must constantly exercise vigilance as they face consequences if performing illegal work. The 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) implemented employer sanctions for the hiring of undocumented workers, while the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) heightened these sanctions and its enforcement (Gentsch & Massey 2011). These laws, and an increasingly harsh anti-immigrant sentiment, have infiltrated the low-wage labor market and are changing industries that rely heavily on immigrant labor. In these sectors, the need to protect employers from the risks associated with hiring undocumented workers has hastened the shift to subcontracting and other forms of non-standard work arrangements, creating a temporary female labor force. 11.8 million immigrant women workers in the United States account for more than seven percent of the total U.S. labor force (ImmigrationImpact), many of whom are undocumented and don’t receive appropriate compensation or working conditions due to harsh immigration laws.

The push for more productive economies has increased the concentration of undocumented workers into the “un-skilled” and undervalued jobs. In 2005 it was estimated that twenty-three percent of all U.S. low-skill workers were undocumented (Flippen 2014). Since IRCA and IIRIRA were implemented to prevent the employment of unauthorized workers, it is expected that undocumented women work at lower paid rates than their legal counterparts. However, while U.S. immigration laws have failed to fully prevent illegal employment, they have most certainly contributed to the continual hiring of undocumented workers. These laws have created such difficulties for undocumented immigrants that their working limitations can deeply affect other aspects of their social lives, making it important to take into consideration a woman’s legal status when evaluating her choice and possibilities employment.

For example, looking at Mexican workers, as they account for one-fourth of all women immigrants (American Immigration Council), enforcement of the IRCA and IIRIRA has pushed Mexican workers and their employers further underground and outside of the formal labor market, leaving employers and employment benefits unsupervised and unregulated. This means undocumented immigrants have no civil or labor rights and temporary workers have severely constrained rights. These migrants and undocumented workers who compete in the same labor markets therefore have minimal opportunities to improve wages and working conditions (Gentsch & Massey 2011). Including the influence of whether or not immigrant women can work, legal status shapes labor supply by directing women into particular occupations that undermine their ability to work full time or in jobs with higher stability.

In Desai’s “The Messy Relationship Between Feminisms and Globalization”, she notes that a woman’s lack of English-language skills and formal education significantly disadvantages her when working towards equal opportunities on a larger scale. This claim coincides with the fact that in years prior to 1996 when immigration reform was not as heavily enforced, statistics have shown that educated immigrants with a strong command of English were more likely to retain a high-skill occupation than those with lower English proficiency or none at all. However, in the present day, because of severe crackdowns on immigration, an educated migrant with a decent command of English does not have as great of an advantage as before as their status as an illegal immigrant hinders chances at higher paying and more stable occupations. However, they would have a higher chance at a more skilled job when they already have established connections in the United States, such as family relations (Gentsch & Massey 2011). Even though undocumented immigrants may be equipped and educated to perform more skilled jobs, illegal immigration status poses a large threat because of the harsh consequences that immigration agencies have implemented in recent decades.

IMMIGRANT LABOR AND FAMILY LIFE

Family is a large social aspect that affects immigrant Latinas’ employment and amount of work. Employers consider women to bear disproportionate responsibility for family care and reproduction, thus immigrant women’s number of work hours depends on household labor. Because of this, studies have shown that women with children are less likely to work than those without children so this can affect a woman’s work visa status if she is thought to potentially not be able to devote enough attention to her job (Flippen 2014). A spouse can also determine a woman’s working status by sharing the burdens of childcare and housework. Her ability to work can also depend on her spouse’s legal status or working visa. When applying for a family visa (a visa that grants one person legal status or a work permit and therefore that person can petition for their family to be reunited with them in the new country), men are typically awarded such visas as burdens of childcare are not thought to be an issue if the immigrant were to reside and work in the United States. These men leave their families behind, often their wife and children, with little economic support in their home country. If the wife were to find a job in her home country, dependence on her husband would be questioned and she would not be considered someone in need of reuniting with her husband, and would therefore be denied immigration status. Furthermore, families that arrive in the United States after their head of household are not granted working visas as they are still considered dependents, forcing the family to survive solely on one income. If the situation is dire, people turn to underpaid, illegal labor to pay the bills. These jobs are undervalued and the U.S. immigration system does not consider them skilled jobs that warrant a work visa, making their citizenship status all the more volatile (Valoy 2013). Women that are highly educated or worked skilled jobs in their home country are forced to accept the low wages and poor quality working conditions. Presence of highly educated women in low-skilled jobs further proves the difficulties of receiving legal working status (Adsera & Ferrer 2014). Undocumented women’s positions in the U.S. economic and political system undermines their ability to leverage gains for their personal and familial development and well-being, whether in the United States or abroad. The rigid gender roles that are present in the United States’ immigration system serve to further create barriers for women to achieve well-paid and legal work.

As mentioned earlier, immigrant women’s jobs are concentrated in domestic and agricultural work. Conflicts between work and family can differ depending on the occupation as some jobs are more flexible when it comes to hours and taking care of a worker’s own family. More flexible work such as jobs in childcare or domestic work may allow a woman to work, while simultaneously taking care of her children, i.e. bringing her child to work with her in place of paying for a sitter. If a woman is a single mother residing alone in the United States, she may be more inclined to work more hours as she does not have to devote extra time to taking care of her children and her home (Flippen 2014). The incentive of sending money back to her family may also be a driving factor that affects the type of job that she is willing to take. Considering these constraints gives more insight into how family structure can further shape an immigrant woman’s employment options.

CONCLUSION

The gender biases that are present in the immigration system make it difficult for women to obtain well-paid and valued jobs that would greatly benefit them when starting a new life in a new country. Not only do the gender biases within the immigration system harm immigrant women, but the harsh laws implemented by the immigration system force both men and women alike into jobs with poor wages and working conditions, increasing the difficulty of starting a new life in a new country. Livelihoods are at stake when people are unable to procure well paid jobs that support their families and lives in a new country. Expulsion of gender bias and harsh immigration laws would greatly improve the quality of life for many Latina immigrants.

Works Cited

Adserà, Alícia, and Ana M. Ferrer. “The Myth of Immigrant Women as Secondary Workers: Evidence from Canada.” The American Economic Review 104, no. 5 (May 2014): 360–64. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.5.360.

American Immigration Council. “Immigrant Women and Girls in the United States,” September 10, 2014. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/immigrant-women-and-girls-united-states.

American Immigration Council. “The Impact of Immigrant Women on America’s Labor Force,” March 8, 2017. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/impact-immigrant-women-americas-labor-force.

Desai, Manisha. “The Messy Relationship Between Feminisms and Globalizations.” Gender & Society 21, no. 6 (December 2007): 797–803.

Flippen, Chenoa A. 2014. “Intersectionality at Work: Determinants of Labor Supply among Immigrant Latinas.” Gender & Society 28 (3): 404–34. doi:10.1177/0891243213504032.

Gentsch, Kerstin, and Douglas S. Massey. 2011. “Labor Market Outcomes for Legal Mexican Immigrants Under the New Regime of Immigration Enforcement.” Social Science Quarterly (Wiley-Blackwell) 92 (3): 875–93. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2011.00795.x.

Wang, Senhu. 2019. “The Role of Gender Role Attitudes and Immigrant Generation in Ethnic Minority Women’s Labor Force Participation in Britain.” Sex Roles 80 (3/4): 234–45. doi:10.1007/s11199-018-0922-8.

Moghadam, Val. 1999. “GENDER AND GLOBALIZATION: FEMALE LABOR AND WOMEN’S MOBILIZATION”. Journal of World-Systems Research 5 (2), 366-89.

Valoy, Patricia. “Why Immigration Is a Feminist Issue.” Everyday Feminism, December 27, 2013. https://everydayfeminism.com/2013/12/immigration-feminist-issue/.

The Effects of Covid-19 on Immigrants and Non-citizen Women

The coronavirus pandemic has been touted by some as a “great equalizer” due to the fact that people of all classes and backgrounds are being affected, yet this horrible disease is no equalizer. Just as in any social disruption some people are affected much more than others and that can be seen when looking at how immigrants and non-citizens are being treated at this time. Immigrant women in the United States, especially Latinas, have been hit much harder than the average american. This is due to many factors including cultural expectations, gender roles, and the types of jobs many immigrant women fill.

Immigrants and noncitizens in general have been impacted much more severely than native born people. There are many factors that put immigrants at a higher risk to contracting Covid-19. Immigrants generally have higher rates of poverty and work in jobs that social distancing is difficult. On top of that immigrants generally have lower seniority in their job and as a result less power. Immigrants will also have fewer networking connections in the country making it harder for them to find a new job. (Scarpetta, Dumont, and Liebig)

Immigrants have also had to battle against increased xenophobia in the time of the pandemic. There are many people who still call Covid-19 the “chinese virus”. Though many immigrants and noncitizens in the country are not of Asian descent there is still a belief that it is the fault of immigrants for bringing Covid-19 to American. This is not just a problem in America but across the world as the United Nations notes “ migrants and refugees are among those who have falsely been blamed and vilified for spreading the virus”(United Nations).

The connection with immigrants to disease if not a new one. In the essay ‘“Anchor/Terror Babies’ and Latin a Bodies: Immigration Rhetoric in the 21st Century and the Feminization of Terrorism” which was written in 2014 it is mentioned that there is a stigma around immigrants and a belief that they “”immigrants enter the country illegally,” “take American jobs,” and “bring diseases.”” (Lugo-Lugo & Bloodsworth-Lugo, 5) This belief of immigrants being bringers of disease has been around for many years but is being magnified due to the current pandemic. Putting the blame solely on immigrants is not only inaccurate but dangerous. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) “stigma can drive people to hide their illness to avoid discrimination, preventing them from seeking immediate health care.” (United Nations) This stigma just leads to the virus being spread more. Though the group facing the most backlash during this time are people of Asian descent, all immigrants are feeling the increased hostility being pointed at them.

The International Office For Migration (United Nations) reports that as much as 74% of the service industry is filled by migrant women in North America. This includes jobs such as domestic work, janitorial work, and many more. The service sector has been hit extremely hard by the pandemic and as a result have caused many of these women to lose their jobs, or at the very least put their jobs in jeopardy. Those who do not lose their jobs must risk their health in order to earn income. The IOM reports that during times of crisis immigrant workers face a higher degree of exploitation due to the fact that they are more reliant on their employer. Migrant women are also more likely to live in crowded conditions making them more susceptible to virus spread. The combination of a higher rate of exploitation and living in more cramped conditions is a potentially lethal one. This means that latina women are more likely to contract the disease at work and bring it home with them. The close conditions they live in are perfect for covid spread meaning it is likely most if not all if the people they live with will contract the disease. On top of that many undocumented immigrants fear getting tested for two main reasons. One that they are afraid to put down their information to get tested due to the fact it may cause ICE to be alerted of their whereabouts. Even though many states do not require undocumennted people to leave information many are still distrusting of this. And two that these women cannot afford to take two weeks off of work. More than this they risk losing their jobs all together if they cannot work for two weeks. On top of this undocumented immigrants are not eligible for support the government is giving during the pandemic, including but not limited to stimulus checks. This creates more pressure on them to work as it is the only way for them to make enough income to survive in this difficult time. This danger is more than just an issue for immigrant women but the population as a whole. Due to the extremely minimal support the country gives to workers like latina immigrants and undocumented people it encourages them to go to work even if they are sick. This perpetuates the spread of the virus. Though many may look at this as a “immigrant problem” in reality it is a public health issue. The governments unwillingness to help immigrants and undocumented people is ultimitly making Covid harder to control.

A part of the pandemic that has put a lot of strain on immigrant families is children being out of school. In many places children are doing school from home via computer in order to slow the spread of the disease. Though this is an important step in slowing the spread it puts a lot of pressure on immigrant families, the mother in particular. This is due to the fact that the mother is expected to take care of the children. The first big obstacle is that The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development finds that up to 40% of native born children in immigrant families do not speak the “host country language” at home (Scarpetta, Dumont, and Liebig). This leads to a language barrier for the parents and what the teacher is trying to say. This makes it more difficult for parents to help their children with their schoolwork, something that during the pandemic they are increasingly being expected to do. The same study finds that immigrants and noncitizens are also less likely than native born parents to have at their home access to a computer, WIFI connection, or a quiet place for the children to do work. All of these things pose a problem for immigrant families who have children in school.

The problem also arises of who will watch the children now that they are not in school. This is causing many latinas to leave the workforce to take care of their families but this is not an option for everyone. On top of this many immigrant families are faced with having to find out ways for their children to go to school if they do not have a WIFI connection. A story that went viral this year showed the struggles some immigrant families face. The photo, which I have posted below (the faces of the girls have been blocked out to protect their privacy), shows two young girls sitting in front of a Taco Bell doing attending school due to the fact that they did not have internet access at home (Ebrahimji). As was noted in a tweet by LA City Councilmember Kevin de Leόn, these girls live in California which is also home to the tech capital of the world, Silicon Valley (de Leόn). The juxtaposition of these two girls being desperate for WIFI so they can attend school and the pinnacle of technology existing simultaneously within the same state is a prime illustration of the stark internet divide. This divide impacts latinos with 40% not having access to the internet in the United States. It was later discovered that the children were being raised by a single immigrant mother who worked everyday to try to support her family. On the weekdays she works as a berry picker and on off days she sells flowers to make money. It was also learned that they live in a one room apartment that they were about to be evicted from. Luckily the tweet going viral caused over $100,000 dollars to be raised for the family. Though that story has a happy ending there are many families in similar situations who are not lucky enough to go viral. If they had not gone viral it is almost certain that despite the mother working tirelessly everyday to support her children they would have become homeless.

The NPR story “My Family Needs Me” (Horsley) looks at three Latina women who are no longer employed due to this pandemic. It also attempts to shed light on possible reasons Latinas are being affected so greatly. Many women were forced to leave the workforce in the past year yet Latina were almost three times more likely to leave their jobs than white women, and four times more likely than afican americans. Between August and September Latina women in the labor force force decreased by 2.7%, while women in general in the workforce only dropped by 1.2%.

Outside of the types of jobs Latinas are in, culture plays a role in the decreasing number of Latinas in the workforce. As the title suggests a large reason many Latinas are leaving the workforce has to do with the societal expectations that the mother will take care of the family. This drop can be partly attributed to the cultural pressure felt by latina women to fill the traditional gendered roles of being the caretaker of the children, who are now home more than ever.With the pandemic many children are out of school and need someone to watch them and culturally it is often expected that the mother be the one to hold this responsibility. One of the women named Sabrina Castillo interviewed said, “there’s something about — in a Latino home — the matriarch, the mother that needs to be home.” She made the decision to leave the workforce in August despite saying that she enjoyed her job. She even said that “I respect stay-at-home moms. But it wasn’t part of my DNA”. Despite her want to keep working, the cultural belief that she needed to be home to take care of her family won out. Castillo’s story is not unique, many women are leaving or choosing not to reenter the workforce due to cultural pressures. It is believed that the man should be the financial provider while the wife should take care of the home. This is shown in the fact that in September around 324,000 Latinas left the workforce while 87,000 Latino men joined the workforce. The pandemic is causing more pressure on women, Latina women in particular, to fall back into traditional gendered roles.

There is a larger concern that these women leaving the workforce will not be a temporary event but more long term. Before the pandemic the number of Latinas in the workforce had been steadily increasing for decades. There are worries that the longer the pandemic continues the less likely it is for those women to return to the workforce. The Federal Reserve governor Lael Brainard was quoted as saying, “If not soon reversed, the decline in the participation rate for prime-age women could have longer-term implications for household incomes and potential growth” (Horsley). The longer women are away from the workforce the harder it is for them to reenter which may cause this decline to have a longer lasting impact than just the pandemic. This has the potential to counteract the fact that before the pandemic the amount of latinas in the workforce had been steadily increasing for years. This could drive many latina women back into gendered roles that they had worked to escape and even discourage other latinas from joining the workforce altogether.

The pandemic has only made the wealth and privilege schisms in our country more pronounced. This is not a “great equalizer” but should instead be seen as a “great stratification”. All the pandemic has done is make it so people like latina immigrants who were already struggling are struggling the hardest. Everyone has been impacted by this pandemic, while some people are upset they cannot see their friends and family, others are fighting to not be homeless. It is important to remember that for some people this pandemic is more than just an inconvenience but something threatening their entire way of life.

Works Cited

Ebrahimji, Alisha. “School Sends California Family a Hotspot after Students Went to Taco Bell to Use Their Free WiFi.” CNN. Cable News Network, September 1, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/31/us/taco-bell-california-students-wifi-trnd/index.html.

Horsley, Scott. “’My Family Needs Me’: Latinas Drop Out Of Workforce At Alarming Rates.” NPR. NPR, October 27, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/10/27/927793195/something-has-to-give-latinas-leaving-workforce-at-faster-rate-than-other-groups .

Kevin de Leόn (kdeleon), “Two students sit outside a Taco Bell to use Wi-Fi so they can ‘go to school’ online.This is California, home to Silicon Valley…but where the digital…,” Twitter, August 28, 2020, https://twitter.com/kdeleon/status/1299386969873461248.

Lugo-Lugo & Bloodsworth-Lugo “‘Anchor/Terror Babies’ and Latina Bodies: Immigration Rhetoric in the 21st Century and the Feminization of Terrorism.”

Scarpetta, Stefano, Jean-Christophe Dumont, and Thomas Liebig. “What Is the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Immigrants and Their Children?” OECD, October 19, 2020. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/what-is-the-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-immigrants-and-their-children-e7cbb7de/.

“COVID-19: UN Counters Pandemic-Related Hate and Xenophobia.” United Nations. United Nations. Accessed December 9, 2020. https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/covid-19-un-counters-pandemic-related-hate-and-xenophobia.

“The Additional Risks of COVID-19 for Migrant Women, and How to Address Them.” Regional Office for Central America, North America and the Caribbean, April 24, 2020. https://rosanjose.iom.int/site/en/blog/additional-risks-covid-19-migrant-women-and-how-address-them-0.

The Struggles Faced by Female Immigrants and Non-Citizens in Accessing Health Care in the United States

Health care has been a controversial topic in the United States for many years. Some believe that healthcare is a human right while others believe that it should remain completely privatized. Wherever a person stands on this debate it is hard to deny that some people are negatively impacted more than others in the current system. One of the hardest hit groups in the United States is immigrants and noncitizens, especially women within these groups.

The struggles of immigrants receiving healthcare is not the same nationwide. Instead many of the policies surrounding the treatment of immigrants is handled at a state level. This means depending on the state they live in an immigrant may have a harder or easier time getting health care. An immigrant’s access to healthcare is not as simple as it may appear. Instead the level of access to healthcare is connected to how criminalized immigrants are within the state. As is noted in the article States with fewer criminalizing immigrant policies have smaller health care inequities between citizens and noncitizens, “States with fewer criminalizing immigrant policies have smaller health care inequities between citizens and noncitizens.” (De Trinidad Young)“Criminalization policies” refer to the level that a state views noncitizens doing daily activities as a crime. In places with high surveillance on noncitizens and attempts to find and deport them even if they have committed no crime is a place with high criminalization of noncitizens. In places like this immigrants are understandably less likely to seek medical aid. This is because going to a public place such as a hospital where you have to put down information they face a risk of deportation. So many noncitizens in places like this decide that they would rather suffer and not go to the doctor than risk deportation.

Even though immigrants’ access to healthcare varies state to state there are some patterns across the United States that begin to shed light on the inequalities that immigrants face when it comes to healthcare. Both noncitizens and immigrants are less likely to have healthcare than people born in the United States. This lack of healthcare means that immigrants have to pay for visits to the doctor out of pocket. This results in less visits to the doctor as many are not able to afford the sick visit. The lack of access to healthcare can be seen in how children are affected. About 45% of children born to undocumented immigrant parents, regardless of their own citizenship status, do not have health insurence. This is compared to the only 8% of children whose parents were born in the United States who lack health insurance (Gusmano). There are some options for immigrant families to try to enroll their child with healthcare but there are many challenges. Often enrolling risks the family being brought to the attention of authorities and as a result deported. The result is that these children are often not brought to the hospital in a timely fashion. This means that immigrant children make fewer visits to the emergency room than children of native born citizens but are often far sicker when they arrive. This also results in immigrant children having a higher rate of hospital admission for avoidable conditions (Gusmano).

As a result of immigrants and noncitizens having a greater struggle with health care, women of these groups are hit especially hard due to their lack of sexual and reproductive health needs not being met. Of immigrant women in the United States around half are in reproductive age, meaning between the ages of 15 and 44 (Hasstedt). Though there is limited research available on how female immigrants’ sexual and reproductive health is handled there are some patterns that emerge. A smaller proportion of immigrant women use sexual and reproductive health services than the average american woman. The Commonwealth Fund, an organization dedicated to promoting more equal access to the healthcare system, notes that, “studies indicate immigrant women may be at heightened risk for some pregnancy- and birth-related complications” (Hasstedt). This could be attributed to the fact that there are more obstacles for them seeing doctors. Without proper healthcare coverage many cannot afford to have routine checkups while they are pregnant and as a result it can take longer for a doctor to diagnose a possible health risk. A program that aims to help low income families is the Children’s Health Insurance Program, also known as CHIP. This help could mean that immigrants are allowed to visit the doctor regularly while pregnant and catch possible problems with the pregnancy earlier. The problem is that despite it being a national program only 16 states allow women to use these services regardless of immigration status (Hasstedt). Even if a woman is in the United States legally that still does not guarantee that they can use these services as in 25 states a woman must have had legal residence in the United States for at least five years. In these same 25 states a woman must also have had legal residence in the United States for at least five years to qualify for Medicaid. Women who are protected under DACA are never allowed to receive these benefits, no matter how long they have lived in the United States. Even if these women happen to live in a state where they receive CHIP coverage, it only applies to pregnancy so if they have any other health issue they will still not be covered.

The problems listed are more than just statistics but very real challenges immigrants, especially women face every day. The National Woman’s Health Network discusses a story of an immigrant woman who they simply refer to as Sophia. Sophia is an undocumented Latina living in Texas with her husband and children. Sophia and her family would qualify for medicaid based solely on their income yet they are blocked from it due to their immigrant status. Her children were born in the United States and as a result are US citizens but despite this they are not registered for any health care. This is because registering them would risk Sophia and her husband being discovered by authorities and deported. A few years ago Sophia began suffering a gynecological issue that put her in tremendous amounts of pain. There are very few places in Texas that serve health needs for undocumented women but they were out of reach and too expensive for her. Because of this Sophia continued without treatment until the pain became too much and she grew desperate. She believed that her only option was to seek medical treatment back in Mexico where it would be cheaper. She payed a “coyote”, which refers to a person who helps to smuggle people across the US Mexican border, to help her re-enter Mexico. Sophia risked everything in order to have her health needs met. If she was caught she would have been deported. Outside of the legal dangers crossing the border is a dangerous journey, especially for women. There are high rates of sexual violence against women crossing the border. The exact number of how many acts of sexual violence are committed for women crossing the US Mexico border is unknown due to the low rates of reporting these crimes. Acts of sexual violence are already under reported but these women risk being deported if they report to authorities what happened. For stories about sexual violence that women have faced while crossing the boarder I suggest reading the New York Times article ‘“You Have to Pay With Your Body’: The Hidden Nightmare of Sexual Violence on the Border” by Manny Fernandez. We do not know what happened to Sophia after this procedure due to the author wanting to protect Sophia’s identity. Even if everything went perfectly for Sophia the fact that she would have to risk so much due to a lack of healthcare shows the impacts of the deep problems within our healthcare system. No one should be forced to risk their life and their safety to receive medical care. Though Sophia’s story exemplifies many of the problems immigrant women have faced her story is in no way unique.

A problem that is too often overlooked is how immigrant women are treated while in an ICE detention center. The New York Times Article Immigrants Say They Were Pressured Into Unneeded Surgeries looks into the terrible events that took place in a Georgia ICE detention center. Earlier this year a whistleblower revealed some of the inhuman practices around women in the Irwin County Detention Center in Ocilla, Georgia. The whistleblower claimed that from this detention center many women were given full or partial hysterectomies without consent and more than medically needed. A hysterectomy refers to the removal of a woman’s uterus and sometimes the surrounding structures. Many women claim that they were not aware that this surgery was being done to them and claim that it was not needed. All of the surgeries were completed by the same doctor, Dr. Mahendra Amin. Notably this is not Dr.Amin’s first instance of being accused of overtreating patients. In 2013 he along with several other doctors were sued by the department of justice for overbilling Medicare and Medicaid due to, among other things, unnecessary surgeries. It was reported that he would perform unneeded surgeries on terminally ill patients and then overbilling Medicare and Medicaid for them. He and the fellow doctors were ordered to pay $520,000 while the defendants were allowed not to admit fault. Despite this knowledge he was the primary gynecologist that women within the Irwin County Detention Center were sent to.

After the complaint was filed five gynecologists reviewed the cases and all agreed that Dr. Admin consistently overstated the size and risks associated with the cysts on the females’ reproductive organs. They also reported that he consistently recommended that surgical intervention was the best course of action, even when it was not medically necessary and there were non-surgical routes available. Dr. Sara Imershein, who is a clinical professor at George Washington University and the Washington, D.C., chair of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, was asked for the article her thoughts on the treatments to which she replied, “there would have been many avenues to pursue before rushing to surgery, Advil for one”.Worse than the over aggressive treatment many of the women were unaware of the severity of the surgery and did not consent to it.

A woman in the article simply referred to as Yuridia recounts her heartbreaking story around Dr. Admin’s mistreatment. Yuridia is a 36 year old immigrant from Mexico who when she was taken in by ICE complained about having a pain in her rib as a result of her abusive boyfriend hitting her. They sent her to Dr. Admin for a medical exam. She recalled the incident saying, “I was assuming they were going to check my rib. The next thing I know, he’s doing a vaginal exam.” Dr. Admin wrote in his notes that cysts on her ovaries that needed to be surgically removed. He also wrote that she was complaining of heavy menstruation and pelvic pain despite Yuridia later claiming that she never reported those symptoms. Yuridia claimed she was misled about the nature and need for the surgeries. She was expecting a minor surgery to be performed vaginally. She was shocked when she woke up from her surgeries to find that three incisions had been made on her abdomen and that she was missing a piece of skin from her genitalia. Three days after her surgery, while she was still recovering, Yuridia was deported. Later pathology showed that Yuridia did in fact have cysts but only small ones that are common in women. Her cysts were not dangerous and the gynecologists who reviewed the case all agreed that there was no need for surgical intervention. Yuridia’s story is not unique and sadly we will never know how many women in detention centers across america have faced similar treatments. These procedures were only revealed via a whistleblower, how many centers are there where people remain silent.

The experiences of immigrants and noncitizens vary drastically within the United States but all face some degree of difficulty. The debate over healthcare has been extremely politicized and many politicians on the right have used the fear of “socialized medicine” as a fear tactic. For a minute I want to take politics out of this and ask that you think of this not as an issue of governmental systems but a question of morality. Is it right that people within the United states do not get the medical help they need out of fear of deportation? Is it fair that children who are citizens of the United States are not taken for medical help because if they are they risk losing their parents? Is it fair that there are now women who have had their uteruses removed without their consent? In a world that is so politicized it is hard to not think of things in a political lens, but not doing so clouds the fact that many people are suffering. That is why I am asking you to not think of the people above as immigrants or “illegals” but simply people desperately needing help from a system that has failed them.

Works Cited

De Trinidad Young, Maria-Elena and Hiram Beltrán-Sánchez and Steven P. Wallace. “States with fewer criminalizing immigrant policies have smaller health care inequities between citizens and noncitizens.”BMC Public Health, Vol 20, Iss 1, Pp 1-10 (2020)

Dickerson, Caitlin, Seth Freed Wessler, and Miriam Jordan. “Immigrants Say They Were Pressured Into Unneeded Surgeries.” The New York Times. The New York Times, September 29, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/29/us/ice-hysterectomies-surgeries-georgia.html.

Fernandez, Manny. “’You Have to Pay With Your Body’: The Hidden Nightmare of Sexual Violence on the Border.” The New York Times. The New York Times, March 3, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/03/us/border-rapes-migrant-women.html.

Gusmano, Michael K. “Undocumented Immigrants in the United States: Use of Health Care.” Undocumented Immigrants and Health Care Access in the United States, 2012. http://undocumentedpatients.org/issuebrief/health-care-use/.

Hasstedt, Kinsey. “Immigrant Women’s Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Coverage and Care in the United States: Commonwealth Fund.” Immigrant Women’s Access to Sexual & Reproductive Coverage & Care | Commonwealth Fund, November 20, 2018. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2018/nov/immigrant-womens-access-sexual-reproductive-health-coverage.

“For Immigrant Women, Health Care Remains Out of Reach.” NWHN, October 29, 2015. https://www.nwhn.org/for-immigrant-women-health-care-remains-out-of-reach/.

Mothering Across the Mexican-American Border

Immigration and Motherhood

What does it mean to be a mother? Realistically, there cannot be a sole, specific definition for motherhood as this definition varies from woman to woman. With that being said, one could generally define a mother as someone who births, nurtures, and cares for their child. What happens to this definition when mothers cross borders without their child? Does the absence of their child during and after migration make them any less of a mother? Immigration has reshaped motherhood. However, it is important to note that this reshaping yielded thoroughly different results for migrant mothers and for American society.

After the events of 9/11, terrorism began to be associated with ‘perceived’ illegality in the United States (Lugo-Lugo and Bloodsworth-Lugo, 2014). This is to say, the bodies of migrant women were transformed into weapons of terrorism. The weaponization of bodies has stripped migrant women from their motherhood altogether as it deems them as nothing more than mere objects who pose a threat to the American public. The United States has used immigration as a tool to dismantle the concept of motherhood by completely dehumanizing migrant mothers. Nonetheless, for migrant women, immigration and mothering across the border only highlights their strength and courage. Melanie Nicholson states, “Latin American immigrant women are operating within a conceptual framework of motherhood that differs from the ideal of exclusive motherhood considered normative from a white, middle-class perspective” (14). By migrating without their children they have not been deprived from motherhood, they have just become transnational mothers.

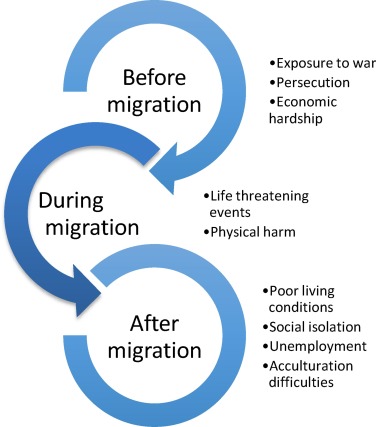

Transnational Motherhood

The concept of transnational motherhood stems from immigration as it refers to the way migrant women keep in touch with their motherhood even after they decide to migrate without their children. In this sense, motherhood is not stripped from migrant women, but reconstructed in such a way that they still can be mothers from afar. Maria Rosa Sternberg and Charlotte Barry held a study of Mexican migrant mothers in which they define transnational mothers as “those women who migrate from poor to developed nations to escape extreme poverty, political persecution, or other oppressive socio-political constructs. In doing so, they consciously leave their country, culture, family, and children. Latinas who become transnational mothers often find themselves in life-threatening situations, crossing dangerous borders as they migrate illegally to the United States” (2). It says a lot that migrant mothers would rather put themselves through life-threatening situations than stay in their home country. For transnational mothers, the end goal of crossing the border and preparing themselves to face the possible consequences of doing so is building a better future for their children. To further prove this point Sternberg and Barry proclaim, “Despite knowing that the trip north would be harsh and dangerous, all of the women still believed that illegally immigrating to the United States was the only way to provide their children with the opportunity for a better life, one free of poverty and violence” (4). Although miles apart, transnational mothers are still a very active presence in their children’s lives. Technology allows for constant communication between mothers and their children which facilitates mothers still being a role model for their children (Nicholson, 2006). Even though leaving their children behind and living alone can prove to be mentally and emotionally challenging for mothers, migrating is a way for them to withdraw themselves from dangerous situations in their home country all while having the ability to provide for their children.

The Decision to Migrate

There are an abundant amount of reasons as to why women choose to migrate. However, in the 2011 study introduced above, Sternberg and Charlotte reveal that “Seven essential themes emerged as the participants narrated their heart-rending stories. These themes include: living in extreme poverty, having hope, choosing to walk from poverty, suffering through the trip to and across the US-Mexican border, mothering from afar, valuing family, and changing personally” (3). Poverty is one of the most influential factors for mothers when they consider migrating. By migrating and getting a job in the United States not only can they save up money for their children to have a proper education, but they can achieve bigger financial goals. Melanie Nicholson proclaims, “By working for a period in the United States, mothers are literally providing food for their children but are also constructing visions of their children’s futures that would have been impossible without migration” (21). Migration opens the door for new opportunities for mothers and their children. Unfortunately, the media has created a negative portrayal of migrants which is solely based on stereotypes (Lugo-Lugo and Bloodsworth-Lugo, 2014). This is to say that in American society, when transnational mothers migrate they pose a threat to the public when in reality mothers migrate in a hopeful attempt of finding a better life for themselves and their families.

Crossing the Border

According to the United Nations, approximately 2,500 people have died attempting to cross the border since 2014 (United Nations, 2020). In 2019 alone, there were 497 recorded deaths on the US-Mexico Border (United Nations, 2020). This is a shockingly high number, however, it is very likely that this number is incorrect and in reality could be much higher due to the possibility of missing reported fatalities. Even though the United States is the most desirable destination in terms of migration, crossing the US-Mexican border is one of the riskiest and deadliest trips one could undergo (United Nations, 2020). While crossing the border, transnational mothers in Sternberg’s and Barry’s study reported “enduring thirst and hunger, walking the desert day and night, climbing the seemingly never-ending mountains, tolerating the merciless treatment of the coyotes, weathering the inhospitable environment, and fearing apprehension were memories indelibly imprinted in their minds” (3). It is of no surprise that the trip across the border is extremely tough. The Trump administration has made the trip even tougher by enacting various brutal immigration policies. In 2018, the Trump administration set up a “zero tolerance” policy which was meant to further discourage illegal entry to the United States (Padilla-Rodriguez, 2020). However, in enacting such policy the 45th President of the United States has divided hundreds of families at the border. As a matter of fact, there are currently about 545 children who have yet to be reunited with their parents (Padilla-Rodriguez, 2020). Jeremy Raff, a journalist for The Atlantic, states those caught crossing the border are transported to “the station known among immigrants as the perrera, or ‘dog pound’, because of the chain-link cages used to hold them,” (Raff, 2018). This is another example of how the United States has dehumanized migrants and one of the main reasons as to why mothers refuse to migrate without their children. Children separated from their families at the border can suffer from severe trauma. Mothers cannot contact their children despite their frequent demands for justice. In his article, Raff discusses the story of Anita, a migrant mother who got her six-year-old son, Jenri, taken away from her at the border. At detention centers, “kids are reportedly barred from touching even their own siblings, depriving them of an essential way to soothe themselves in crisis” (Raff, 2018). No mother wants to have their children taken away without knowing if they will ever see their children again. Especially, if their children will be neglected and thrown into isolation in detention centers. Although transnational mothers sometimes experience extreme isolation in the United States because it is a completely different culture than the one they are used to (Nicholson, 2006), some mothers would prefer dealing with such isolation than putting their children in danger.

Depicting Transnational Motherhood Through Art

This drawing is a collaboration with my dear mother. At a point in time, my mother herself was a transnational mother. She migrated into the United States alone in hopes of paving the way to a better and brighter future for me. I have so much respect for her and her decision to migrate alone that this drawing is my way of saying thank you to her. I took her experiences as well as some aspects discussed above and incorporated them into my drawing. I purposely decided to leave the woman’s face blank so all transnational mothers could somewhat connect to this piece. Here we see a woman wearing what resembles an oversized jacket. The jacket is meant to appear big to highlight the heavy burdens that migrant mothers carry on their shoulders. The middle of the jacket, where the zipper would be, does not touch to symbolize the US-Mexican border. The only place the jacket touches is at the very top. Here we have a small human figure crossing from one side to the other. The human figure is also the woman’s necklace to showcase that mothers go on this journey all alone. Inside of this jacket we have different factors that influence migration. On the one hand, the left side of the jacket is meant to symbolize their home country. Specifically, their family and the poverty that they face which is what drives mothers to migrate. On the other hand, the right side of the jacket is meant to symbolize the United States. Here we have opportunities for education, employment, and the American Dream as a whole. The jacket itself is painted different shades of blue to resemble a universe and showcase that all of the things inside of the jacket are part of the mother’s world and thus affect her in some way or another. The woman in my drawing has a crown to highlight the strength that migrant mothers have in starting from zero in an unknown country just so their children can have the future they always dreamed of.

To finish off I would like to leave you all with a quote that heavily influenced my overall blog post and specifically my drawing,

“These three factors—the arduous journey, the hard work and isolation experienced once in the United States, and the years spent away from their children—point to a good deal of suffering on the part of these mothers, but also to their remarkable courage, perseverance, and determination” (Nicholson, 2006).

Works Cited

Lugo-Lugo, Carmen and Bloodsworth-Lugo, Mary. “‘Anchor/Terror Babies’ and Latina Bodies: Immigration Rhetoric in the 21st Century and the Feminization of Terrorism.” Journal of Interdisciplinary Feminist Through, vol. 8, no.8, 2014, pp. 1-21. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/jift/vol8/iss1/1.

Nicholson, Melanie. “Without Their Children: Rethinking Motherhood Among Transnational Migrant Women.” Social Text, vol. 24, no. 3, 2006, pp. 13-33. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1215/01642472-2006-002.

Padilla-Rodrigues, Ivon. “The U.S Separated Families Decades Ago, Too. With 545 Migrant Children Missing Their Parents, That Moments Holds a Key Lesson.” Time, 2 November 2020.

Raff, Jeremy. “How Trump’s Family Separation Traumatized Children.” The Atlantic, 7 September 2018.

Sternberg, Rosa Maria and Barry, Charlotte. “Transnational Mothers Crossing the Border and Bringing their Health Care Needs.” Journal of Nursing Scholarship, vol. 43, no. 1, 2011, pp. 64-71. ProQuest, doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2010.01383.x.

“2019: A Deadly Year for Migrants Crossing the Americas.” United Nations News, 28 January 2020.